The Cat Read online

Page 2

‘No, certainly not. We’re brighter than dogs. Much, much brighter,’ said the Rat, decisively. Now the Mouse was silent for some time, and in the silence, the Rat felt the foolishness of his own words creep upon him.

‘And the Professor, Rat, eh? Where’s he gone to?’ continued the Mouse, adopting an inquisitorial tone, as if persisting against a class of sullen students unwilling to question the ill-judged simplicity of their beliefs.

The Rat stood up and stretched, his tail snaking across the bin lid behind him like a serpent unleashed from a bag.

‘Who needs humans, Mouse?’ he said shortly, ignoring the Mouse’s question. ‘Always thinking. Inventing things. Getting things wrong. Eating everything in sight. We can do better than that!’ declared the Rat. Then the Rat spun round and leant down to whisper in the Mouse’s ear:

‘D’ye see how quiet it is now? Normally he’d be playing his classical records.’ The Rat imitated the opening bars of Vivaldi’s ‘Four Seasons’ loudly, and then sat back down on the bin lid. The Mouse felt faintly regretful for the strains of the classics. The only sound now was the distant shouting of an American soap opera, barely audible through an open window on the far side of the hedge.

‘With the Professor gone there’ll hardly be time to sleep and then we’ll be off and up again, restlessly looking for food,’ said the Mouse, his voice trembling.

‘Rubbish!’ said the Rat, with the false conviction of someone who was denying his own deepest fears.

‘If the worst comes to the worst, you can always fall back on bins.’ The Rat slapped his foot down on the bin lid, making a hollow booming noise.

‘The Professor didn’t spend all his time rootling around in bins, did he?’ protested the Mouse.

‘He didn’t need to,’ said the Rat confidently. ‘His needs were different from ours.’

The Rat, feeling suddenly impatient with the Mouse, walked to the edge of the bin lid and peered over.

‘Why?’ asked the Mouse.

‘Damn it Mouse I don’t know, do I? I mean that’s just how it is,’ snapped the Rat. ‘I mean some things just ARE.’ The Rat hesitated. Then he grinned in the darkness.

‘Hey, Mouse! Do you remember Animal Farm? You know, the one where all the animals themselves take over.’

The Rat turned around as he spoke, his hand on his hip, his cloak draped stylishly over the elbow.

‘They came to a sticky end, overcome by selfishness, greed and ambition,’ said the Mouse gloomily. The Rat ignored him.

‘We need a firm hand y’know Mouse, someone who knows what’s what. Someone who can get fair shares for all and a decent bite to eat, from the very lowest to the very highest.’

‘Like who?’ asked the Mouse. The Rat stood proudly, his chest out, his whiskers bristling, his snout in the air.

‘Who d’you think, Mousey?’ said the Rat, in a strange, gruff, self-important and faintly military voice which the Mouse had not heard before.

The Mouse, although he still frittered the days away with small schemes and wild dreams, nonetheless found himself checking things rather more frequently than before around the house in the days that followed, as if at any moment expecting some surreptitious and disturbing departure of the biscuit barrel or cake tin as the precursor of a larger and more final exodus.

The Cat was restless too with the way that things were. There was a certain slackness in Mrs Professor’s manner towards him which worried him greatly. It implied a lack of that commitment, that close reciprocity upon which all Cats depended. And there was a certain slovenly approach to the household that annoyed him too. Were he in charge, everything would run like clockwork; there would be rat poison for Rat and the other spongers, breakfast at six and again at eight, and all the chicken wire removed from the hedge so that he could visit the neighbours Cat without snagging his belly.

‘Its an opportunity for change!’ he thought to himself, frustrated that Mrs Professor seemed to see her husband’s death as an excuse for even greater lassitude.

But the Cat was suffering emotionally too. Despite his hard exterior, he was nonetheless a sensitive, if unpredictable spirit. Too often in the days after the death he would find the food coming late, or even worse, not at all. Cruel ironies would occur, when, after a morning fretting for breakfast he would stalk out into the autumn garden to sit and calm his nerves, only to return to find his food had been served, but mysteriously thrown away in the bin before he had had a chance to eat. Then again, Mrs Professor sometimes would absent-mindedly serve breakfast two or even three times in a morning. The Cat would grin and eat his fill, pretending the second breakfast to be the first, forcing down steaming mounds of rabbit until his whiskers reeked of the stuff and just be on the point of staggering away to sleep it off when a further portion would be slapped down in front of him. Then he would sit there all morning, watching the food harden and become inedible before his pallid gaze, unable to comprehend how the realisation of one of his favourite fantasies could in reality be so unpleasant. Then there would be no food for days.

The Cat stalked the house, restlessly miaowing, unable to take pleasure in anything: frustrated by the cool white fastness of the fridge, strangely tempted by the sight of small birds on the patio and fascinated by the dry trickle of the Mouse’s scurryings behind the skirtings. He would lie around gloomily, his fur itching and hot, his tail lashing to and fro.

From time to time he would leap across the lawn and through the hedge, or up onto the return of the house next door, and from there to the roof, from whence he would survey the scene below, balanced astride the ridge tiles; on one side the front garden stretching away to the trees, the lake and the B352 beyond, on the other the swell of the downs breaking away from the back gardens, rising up into the clear Autumn sky.

Beyond the garden, over the back fence, cows pulled at the hay in the meadow. In the alley between ‘Chez Maupassant’ and the house where he sat, he could see the tiny figure of Mouse, as if through the wrong end of a telescope, chasing a biscuit wrapper.

Then the Cat would fall to thinking; what a contrast there was between the gardens beneath him! Although ‘Chez Maupassant’ would always be home, and was undoubtedly the finest place on earth, how sadly it had fallen away under the Professor and his widow! The living had been altogether too easy for everyone, he thought. However next door they had had the will and the resources, the initiative and the drive to lift themselves up! The garden was immaculate; things were constantly being put up and taken down again, paint burnt off, then repainted, then burnt off. It was a constant frenzy of productive activity, while ‘Chez Maupassant’ had spawned only slothful dinners and disgusting literary afternoons which sprawled out onto the long grass, handing a living to the likes of Rat and Mouse.

What was needed was to keep the house clean and free from vermin of all sorts, thought the Cat, and then you would have the sort of environment that would attract the right kind of people. Yes, the right environment, thought the Cat, and reversed up to the chimney stack, rubbing his behind against it to stem the itching with the warm rasp of red brick.

Then one day in mid-October the Mouse was awakened by an unfamiliar noise.

‘Tchaka Tchaka Tchaka Zubba Zubba Ya Ya Get crazy Ya boom Ya boom Ya get crazy now Ya Zubba Booop de Doop …’ went the music as the Mouse struggled from bed, the walls to his room vibrating in time to the beat.

‘My God! What a ghastly noise,’ he murmured, and tried to block his ears.

‘Tcuggga Tchugga Boop Booop Tchugga Booop Booop Booop!’

‘Stop that noise! Stop that racket!’ shouted the Mouse, and ran swiftly down the narrow corrridor behind the skirting and out through his front door without looking to the right or left, so annoyed was he by the intrusion. Several steps out into the living room, the Mouse halted, his body sagging, his mouth open in surprise. The carpets were already up, bound and bundled like hostages taken in combat against the walls, the sofa cushions removed to reveal its innards, bare and u

tilitarian in the harsh light of morning. Of Mrs Professor there was no sign.

The Mouse sprinted for cover under a bookshelf, where he sat shivering with cold and fright for ten or twenty minutes, the noise and the general commotion of removal paralysing his thoughts. Through a small knot-hole he glimpsed the Cat, gliding to and fro with a false nonchalance amongst the items in transit, ducking and weaving to avoid this or that object as it accelerated out into the hall, guided away by the skilled hands of four removal men.

‘Steady now! Steady!’ purred the Cat, whether to himself or to the removers, the Mouse could not tell. Then the Cat’s yellow eyes flicked round, and swiftly homed in upon the knot-hole from where the Mouse was spying on him, as if guided by some magic feline radar. The Mouse saw him change course and slide up, pretending not to speak in the way that Cat’s have, by looking the other way.

‘Mouse. That IS you in there, isn’t it? Isn’t it, Mouse?’ The Mouse tried not to breathe in the darkness, but managed only to create the kind of intense silence that confirmed the Cat’s suspicions of his presence. The Cat’s nose butted the knot hole, exhaling the foul smell of his last fish breakfast into the confines of the space where the Mouse was hiding. The Mouse coughed.

‘We’re moving out Mouse,’ said the Cat. ‘We’re off to Brighton. That’s what she’s said. It’s by the sea, and you know what that means, Mouse.’ The Mouse did not. He reversed carefully in the darkness, checking the bare boards beneath his feet for further knot holes or gaps through which he could slip away to the safety of the underfloor void. The Cat talked cheerfully. The Mouse heard him lie down, his dark and furry side pressed firmly against the knot hole. ‘Oh yes Brighton’s a fine place for a Cat. A stroll down to the pier of an evening, after the catch is in. Mackerel. You ever tried mackerel, Mouse? Mackerel on your whiskers is the finest thing, not that you’d understand. Then roll away to sleep it off on the old girl’s armchair …’

The Cat’s voice echoed in the dark cavity, as the Mouse, feeling with his toe behind him, felt a cool draft of air, pencil thin, blowing up his trouser leg from down below, and, seeking its source, found a hole no bigger than a largish thumb, through which he squeezed with the loss of a few buttons, and crept away under the still talking cat, the noise of shifting furniture booming like thunder all around him.

CHAPTER TWO

THE CAT SINGS TOO LOUDLY

The Mouse awoke to find the house strangely silent, without the normal sounds of the Cat being summoned for breakfast, nor of rushing water, nor of morning radio. He pulled down the counterpane on his bed, hung his nightcap in its usual place, and stepped lightly down the hall behind the skirting, towards his back door and the kitchen beyond. Anticipation of a cat-free world mingled in the Mouse’s mind with apprehension as to how such a world might function, as he stepped outside.

He coughed and stretched and sniffed the air, which chilled his nose. Then he ran to the middle of the floor, where he stopped and sniffed again. The house now smelt of dust from under carpets, of still air, of closed doors and emptiness. Some scents still lingered of things now gone – a vague tang of Cat and catfood, even a hint of pipe tobacco from the dead professor hanging ghostly in the atmosphere. The Cat’s bowl, forgotten and overturned, lay by the cat-flap, licked clean of food.

‘Oh God!’ cried the Mouse. The cooker and several kitchen units had disappeared, but so too had the fridge.

‘Oh my God!’ breathed the Mouse, gripping his nose with both hands in dismay, turning the black and shiny end to and fro between his fingers. Despite the Mouse’s limited knowledge of economics, he could see that the entire infrastructure of ‘Chez Maupassant’ had been destroyed. Up until that moment, wrapped in that imperviousness to circumstance that is the hallmark of the half-asleep, and cheered by the absence of Cat, the Mouse had not confronted the full significance of the removal men for his future life.

Disconsolately, the Mouse trailed out into the living room, which seemed vaster than before, his footsteps a dragging echo, swallowed whole in the unfurnished space where the Professor had put his feet up, watched ‘Panorama’, and dropped cheese inadvertently upon the warm rugs but weeks before. Now uninhabited, ‘Chez Maupassant’ had shrugged off its homely, Edwardian feel.

The Mouse shivered and returned to the kitchen, where he sat down in the middle of a bunch of flowers, imprinted on the lino.

‘Well, at least they could have left something,’ he thought to himself as he sat there. As if in answer to his thoughts, there was a dreadful rattle at the cat-flap, and the Cat poured unexpectedly into the kitchen. The Mouse froze, for a moment uncertain whether it was the Cat, or some other quite different and much more dangerous Cat. He looked carefully. It was the same Cat.

‘What are you up to, Mouse?’ The Cat’s voice was the same; sibillant and all-seeing, with a smoothly dishonest edge of friendliness to it, hinting perhaps at depths of feeling, at sudden lurches of conscience and intellect that were unsafe in the extreme. The Mouse’s mind raced; the Cat should have been in Brighton.

The Cat (like an overgrown settee on gimbals) slid across the kitchen, and the Mouse experienced an alien frisson of complete terror, observing his quivering flanks and brindled low-slung head, his eyes cold. Then his shadow fell upon the Mouse.

‘Cat,’ said the Mouse. ‘I thought you’d gone to Brighton.’

‘She wouldn’t take me, Mouse,’ hissed the Cat. ‘Said I could “fend for myself.” ’ The Cat seemed to leave a special emphasis on the last words. Then he sat down, taking advantage of the Mouse’s hesitation to occupy the space between the Mouse and the door. The Mouse was overcome by the contradictory urges to laugh, to run, and to feel sorry for the Cat. He felt himself on the verge of hysteria. Inappropriate song bubbled in his mouth, accompanied by light, tinkling music in his ears.

‘That’s dreadful, Cat,’ he said diplomatically. ‘Why on earth? How extraordinary! How many years were you together?’

‘Twelve,’ said the Cat bitterly, examining his claws as he spoke. His eyes seemed to look at the Mouse, not, it seemed to the Mouse, as if he were a Mouse, but rather as if he were something else completely. The Cat adjusted his position, and licked his lips. Already he seemed thinner. The Mouse noticed all of this in an instant.

At that point there was a dry gurgle from the sink unit and the sound of the sump on the U bend being unscrewed from the inside, and the Rat leapt out, followed by a gout of sludge and slime, and proceeded to dry himself ostentatiously with a fluffy pure white towel which he carried on his back in a sealed plastic pouch. The Cat was distracted.

‘Hi fellows,’ said the Rat, stepping down onto the lino and walking across it as if the Cat did not exist, to place himself next to the Mouse. The Mouse felt a warm sense of security steal over him, and gratitude. His teeth stopped chattering.

‘Moved out, eh!’ said the Rat, drying his paws, and replacing the towel in its pouch. ‘Lock, stock and biscuit barrel. Just like that. I knew she would. Cat! What are you doing here anyway? Mouse said you were in Brighton!’

The Mouse saw the Rat appraise the Cat’s downtrodden air in one swift glance, and saw him note the slight dusty pallor that now clung to the Cat’s normally glistening coat.

‘Cat’s been told he’s got to f … f … f … end for himself,’ said the Mouse significantly, regaining his voice.

‘Fend for myself,’ repeated the Cat. His eyes were veiled and hurt. ‘I mean I don’t know on what.’ The Cat shrugged expressively at the spot where the fridge had stood, its position marked by an oblong scatter of sticky crumbs and bright-coloured linoleum.

‘Rat’s got some food,’ said the Mouse, very quickly. The Rat glared at him.

‘Its mainly chocolate,’ said the Rat dismissively. ‘We don’t have much of your kind of thing, Cat.’ The Cat hung his head.

‘I’m damned hungry already,’ he said.

‘We’ve got those old vol-au-vent cases with chicken and mushroom filling, haven’t we, Rat. The

Cat could have some of them,’ suggested the Mouse, pleading, and began to pick his toes nervously, and unwisely as it displayed to the Cat his plump pink belly, quivering. The Cat’s eyes seemed to lock onto the belly, and his mouth opened very slightly.

‘The vol-au-vent’s all gone,’ said the Rat. The Cat’s eyes became more veiled than ever, as if a blind had been drawn down inside his head.

Later, the Cat hunched low down, his belly fur soaking up the moisture from the wet grass, his knees trembling with the intensity of his concentration and the cold. A small bird dabbled innocently at the lawn, eating flies that hid amongst the grass stems. The Cat’s eyes had narrowed, so that they now seemed sphinx-like and opaque, with only a small black slit letting the image of the bird into the Cat’s brain. The Cat examined the bird, his mouth slightly open, his pink tongue just protruding, flanked by needlepoint teeth. He liked the way the bird hopped from foot to foot, and the way it dipped in amongst the stems of grass. He liked its innocent unawareness. There was something terribly exciting about the bird, something foolish and alluring! Oh yes, how did one do it? He’d almost forgotten. One step forwards, keeping the tail low, and then WHAMMO! Disgusting! What was he doing?

The Cat sprang, like a tripped rat-trap; his hind legs snapped up, his front legs snapped down and he flew through the air, both paws full out, talons uncurled just as a sense of the wrongness of what he was doing intervened to send him in to land with an unsatisfying thud and a slide amongst the grass stems and the mud and the wet, the only trace of the bird a memory of a brush of feathery wings across the face, almost a provocation in fact.

The Cat stood up and shook himself, looking round to see if anyone had noticed. His heart was pounding, and beneath the fur he had broken out in a cold sweat. The empty windows of ‘Chez Maupassant’ blazed in the brief morning sunlight, uncurtained. The grass stems nodded.

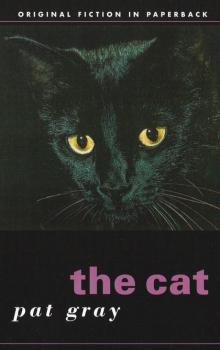

The Cat

The Cat