The Cat Read online

Page 4

‘And why couldn’t we learn to drive, eh,’ said the Cat with that blend of aggression and disdain that the Mouse found so unbearable. ‘What a limited view you have of our capabilities, Mouse. That’s just the sort of moaning talk that’s kept us back. We can do ANYTHING Mouse, with a little practice. Look at the people here, and what they’ve achieved, eh. Look at the lawn. Look at the garden. Admire the car, Mouse. Are you going to stay where you are for ever?’

The Mouse hesitated. Despite everything else, the Cat was so persuasive it was awful. His eyes now were hypnotic, huge, golden, beautiful. The Mouse stared into them, and for a brief moment, found himself believing everything the Cat had said. Mouse at the wheel of a fast car! Mouse in command of a well equipped kitchen. Mouse using the telephone to order meals as he had seen the Professor do.

‘Y’see?’ said the Cat, reading his thoughts.

Even Mouse with his own television set! No, it was too incredible. Suddenly, the spell was broken, and the Mouse found himself far too close to the Cat.

‘Are you in, or out, Mouse,’ asked the Cat. The Mouse hesitated, not because he was uncertain, but because he was taken aback by how certain he felt.

‘Out,’ said the Mouse, decisively. ‘I’ve never heard anything so ridiculous.’

‘Very well,’ said the Cat, in a sinister way which silenced everyone. He paused, and his large yellow eyes seemed to harden. Then, wordless, he strode stiff legged away from the Mouse and off into the darkness, as if the Mouse, the crowd, and everyone else in the universe had ceased to exist, on account of their ill-considered pessimism as to the infinite possibilities for animal advancement.

‘What did you make of that, Mousey?’ the Rat asked after the crowd had broken up. The Mouse found himself vaguely irritated by the Rat’s matiness.

‘It was an absolute disaster,’ he said.

‘You hectored and bullied and no-one believed you, you annoyed the fieldmice, lost the initiative to the Cat and what the hell was all that about the “young fieldvole”, eh?’

‘Its a matter of presentation, Mouse,’ he said. ‘I mean the poor animal was dead anyway.’

The Rat swung around, his Italian suit glinting in the moonlight. ‘OK,’ said the Rat, suddenly angry, and hurt by the criticism that the Mouse had delivered. ‘Look, Mouse I’ve had it just about up to here with your whingeing and moralising. Up to here!’ And the Rat made a gesture, holding his paw to a point well above the end of his black and shiny nose to show how far he was annoyed with the Mouse. The Mouse blinked, and gulped. He could feel tears stinging his eyes. Part of him wanted to hit the Rat, to kick him on the shins and leave muddy stains on the smart trousers. Another part, much the larger part, wanted the Rat to withdraw the remark and apologise, and everything to return back to where it had been.

‘Would it have been better if I’d had a loudhailer?’ asked the Rat.

‘Oh God, Rat,’ said the Mouse. There was a long pause.

‘You think I’m stupid,’ said the Rat, presciently. ‘Don’t you Mouse?’

‘Sometimes you miss the point, that’s all, Rat,’ said the Mouse. But the Rat flared up again.

‘Just because I haven’t had the learning you’ve had Mouse! Never had the opportunity!’ His voice cracked, then the Rat turned and strode off, his coat tails flying, his tail whistling through the wet grass behind him.

‘Rat!’ shouted the Mouse, and began to run after him, but the Mouse was slowed by the weight of the Rat’s new briefcase which he was carrying, together with the folding card table. After a few steps he halted, out of breath. A strange mist had begun to creep upon the lawn surreptitiously, a deepening opacity, a gradual thickening in the atmosphere, a grey vestigious spider’s web of vapour, through which the Rat strode forwards, but the Mouse – submerged beneath and encumbered – found it hard to follow.

‘Rat!’ he shouted. In a temper he lifted the briefcase and hurled it into the ditch. The case bounced with a hollow, leathery kind of noise in the darkness. He clutched at the card table, and one of the legs sprung out awkwardly. The hedgerows had vanished, and the night stars. Only the wet grass remained, dragging at his feet, adhering to his grey fur, the white rime of night frost freezing his ankles, and the Mouse began to feel a certain damp chill enter his heart.

‘Girls,’ said the Tom. ‘I like girls!’ The Cat was at once appalled and titillated. The way in which the Tom said ‘girls’ was somehow so uninhibited and wanton, so violent and cruel and exciting and somehow liberating that the Cat felt breathless. The night was very black, with the lights of neighbouring houses haloed in the mist.

‘Its a good night for girls,’ said the Tom, sniffing the air.

‘Pussy!’ said the Tom, placing his head on one side, very slightly, and listening before making a low growl in his throat. The Cat moved backwards, involuntarily, and his paw struck something in the darkness.

Bending down, and adjusting his eyes to the gloom beneath the hydrangeas the Cat detected the faint glimmer of a polished leather briefcase, and, looking more closely, the name ‘RAT’ embossed in gilt just beneath the handle.

‘Briefcase,’ said the Cat, in explanation. ‘The Rat’s got a briefcase.’ The Cat let out an incredulous laugh (or more correctly laughed inwardly, as Cat’s are entirely humourless in any external sense), then picked up the briefcase in his teeth and tossed it contemptuously away, before moving on, a gradually accelerating sense of excitement building within him, fuelled by the night and the rustle of a faint breeze in the hedgerows.

‘Huh!’ said the Tom, whether about the Rat owning a briefcase, or about the very idea of briefcases in themselves it was hard for the Cat to tell.

‘There’s something else out here,’ said the Tom, still sniffing. ‘There’s some other thing out here too. Some other little bit of tasty nibblies, Cat.’ Tom halted, and breathed in the air as if savouring the bouquet of a newly uncorked wine. ‘Good bit of Mouse can set you up. They’re sad little beasts you know, Cat,’ he said, suddenly reflective. The Tom looked at the stars, his big flat head turning slowly, the sides of his nostrils quivering with faint tiny pulsations, the whiskers stiff. ‘Clever as they come, but, oh dear me your Mouse is dreary! Oh yes, listen to a Mouse for long and you’ll be half asleep and begging for mercy, Cat. They sit around all day reading books and thinking and then they get depressed because they’ve achieved nothing and there’s nothing to show. Always measuring the world against other worlds in books instead of considering it as it is. Oh yes, Cat the best thing to do is to MUNCH THEM UP!’ The Tom began to whisper, and his footsteps became strangely silent. ‘I can smell one now. Y’know what a mouse smells like? I suppose not. Not trained for it. I can definitely smell one now. A sort of a kind of a bookish sort of chicken smell, like a dictionary with the place marked off in it with a turkey sandwich, Cat.’ Then the Tom dropped to the ground, and vanished with a noiseless flick of the tail, like a velvet arrow. The Cat strained to see ahead in the night. Something awful was about to happen. The Cat wanted to cry out, but his lips were dry with an unforeseen sense of crude anticipation. Then he too leapt into the darkness.

All through the next day the Rat could overhear the murmuring sound of argument and altercation, as the garden’s inhabitants debated the affair of the vole, and the Cat’s extraordinary speech at the garage door, and the behaviour of the Rat himself, and even the role of Mouse in the affair. Although the Rat tried to move around quietly, so that he could hear in detail what people were saying, his innate clumsiness however prevented him from gathering anything other than a general impression of fevered debate. It would, he realised, have been a good day to have the Mouse’s intelligence gathering skills at his command.

Several times the Rat went round to the Mouse’s door in the skirting, and knocked and banged, but without result. Thinking perhaps that the Mouse was sulking, the Rat thought little of it, and continued a pleasurable stroll round by the bins and out to the end of the garden where the foul water sump h

ad its exit.

As he wandered, the Rat was stopped from time to time, and questioned further about his views, or asked for information, and soon the Rat found himself embroidering and exaggerating this or that small detail to his own advantage.

Indeed, as time went on, the Rat’s natural skills of hyperbole began to cloud his judgement, and he found it hard to keep track of which particular version of the murder he had told to whom, and to what effect. Nervously, the Rat realised just how inconvenient it was not to have the Mouse there as foil, analyst and general social assistant.

Thus, by five that evening he found himself once more outside the Mouse’s door, hammering upon it as if his life depended upon the result.

‘Mouse! Come on, Mouse! Mouse come on! Open up!,’ he cried, sweat running into his eyes. Looking up, the bare walls stretched, devoid of pictures to the cobweb strewn ceiling beyond. The door remained shut.

An awful premonition came to the Rat, and the Mouse’s words echoed disconcertingly in his head, even though the Rat tried to shake them off by whistling noisily, and clapping his hands together, and saying things to himself like ‘Well now, Rat, let’s just get on with it!’, as he waited outside the closed door. He found it hard to accept that he had rowed with the Mouse. Rat and his old friend Mouse? How had he allowed his vanity to take hold to such an extent that he had left the Mouse in danger?

At length the Rat began to retrace his steps of the previous night to where he had lost the Mouse in the mist. Slowly, scanning the ground, he crossed the lawn, and through the hedges and gardens beyond. In the bright sunlight, the mist of the previous evening seemed almost a fantasy, a night humour brought on by cold and lack of food. However, two thirds of the way across the second garden, almost at the spot where he had parted company from the Mouse, the Rat halted suddenly, and clapped his paw to his mouth.

‘My God!’ he cried, and stumbled down off the lawn into the muddy border. There, lying torn and ripped in the bottom of the flowerbed, was his new briefcase. The Rat picked it up, holding it gently as if it were a child. The catch was broken and the case fell open in his hands, yawningly empty as it always had been. Guiltily, the Rat looked around. The garden was bathed in bright sunlight, the birds were singing, everything was normal. The Rat’s eyes narrowed. Then he scrambled back up onto the lawn, and ran back to the Mouse’s front door, and pushed it in with a crash and a bang. Inside, the bedroom had the scent of a spare room, and the bed had not been slept in. The Mouse’s copy of ‘Animal Farm’ lay open where the Mouse had left it on the counterpane. The Rat scanned the pages, tight-lipped, and then replaced it carefully, before rushing out into the garden once again, where the day was by now innapropriately hot. Then he set about organising more detailed enquiries.

‘Has anyone seen the Mouse?’ he asked.

‘No Sir, not Mr Mouse.’

‘Mr who?’ The Rat became more angry.

‘Form a search party!’ he shouted. ‘Come on, or do I have to do everything myself. Look there’s food in it!’ and with that he led those animals he had managed to gather together to the door of his burrow and flung it open, and tossed bar after bar of chocolate, half eaten vol-au-vents, bread and biscuits out onto the lawn.

‘Eat the lot,’ he shouted wildly, while the animals, murmuring, filled their pockets.

Yet all was not entirely well with the Cat. Little by little he had become aware that small birds previously undisturbed by his careful footsteps would now leap skywards at the slightest noise, even the brush of a tail against tree bark, or an overloud inhalation or exhalation. No longer were there picnics in the garden for families of fieldvoles. Instead, the diminutive and foolish creatures had retreated further from the house, towards the meadow beyond, venturing out only in large disorganised groups, at odd hours of the day or night, crazily armed with anything that came to hand. Although this in itself was not enough to deter a well-resourced Cat, it was nonetheless an unjustified inconvenience.

The Cat now observed that a silence, punctuated by the occasional bellowed insult, would often greet his appearance through the cat-flap. There was respect there, the Cat realised, and yet it was still not exactly what he had wanted. In surveying the deserted, ghostly greensward the Cat felt a gnawing sense of grievance. After all, he reasoned, what had he done wrong? It was bad, yes, but not that bad. And he had got away with it too. But getting away with something, the Cat discerned, was not quite the same thing as it being right.

And another thing; there were the thistles that had begun to grow up between the paving stones of the Cat’s favourite sun-trap. Now, each time he tried to sit down, he found one pricking his bottom, or tickling his privates. Crossly, the Cat inspected the gaps between the paving stones. Why had the weeds not been removed? Someone was slacking somewhere. The paving slabs chilled his bottom too. Far better if the entire garden were carpetted in Axminster! The Cat smiled at the thought. The sun came out, and the Cat’s mood shifted.

What fun it could be though! Fun to romp and gamboll, to toss and bite out there on the cold night lawn with the mist in his fur. And the taste of Mouse, a light, flavoursome meat with a hint of gaminess about it, and a freshness that canned food could only hint at. Who could resist such temptations, and indeed why should one?

The Cat’s eyes focussed in upon the garden, now overgrown with bindweed, like a miniature primeval wilderness it seemed to beckon to him. The garden was his place now, and the role he had acquired in it was right because it felt right. Such issues were not susceptible to moral debate; the idle flutter of mere words, the pale and mousey exchange of mere ideas. The Cat felt that what he had done was right for him, and right for the universe. Eating mice was his place within the time honoured natural order, of that he was certain. And, as if to confirm this, the sun which had been obscured by heavy black cloud all morning, now shone clear into the back garden, warming the patio, and warming the Cat, clear through to his now full stomach. Contentedly he stretched, and strolled towards the boundary hedge, slipping through with an elegant step onto the lawn beyond.

Looking over at the house, the Cat could see someone in the kitchen. The Cat stared. A woman with a kind, oval face was washing up. The radio was playing softly, and the woman was singing along as she stacked the dishes methodically on the drainer. On the table beside her was a half eaten chicken, and the scent of it came to the Cat, blown with the wind. The Cat sat and watched, fascinated by the scene for quite some time. Then he stepped forwards lightly towards the door.

The Rat – in common with all characters who have a certain surface smoothness – had depths within him which quite surpassed those of supposedly more serious creatures, perhaps because that very smoothness kept his emotions unnaturally restrained. Although the animals were kind, and indeed clamoured for the Rat to take a leading role in the hope of cheering him, the disappearance of the Mouse seemed to have burdened the Rat with uncharacteristic feelings of depression and guilt. For days he could be seen slouching, coat buttons undone, turn-ups trailing in the mud, across the lawn, careless of his own safety, whistling half-heartedly, or conversing with another who was no longer present. In the night sometimes the animals would hear the voice of the Rat coming from his burrow:

‘Mouse, no, damn you, not there, not that way!’ or the ghostly cry of ‘Mouse! Watch out! Watch out behind you!’

The animals indeed feared that the Rat might so completely lose his grip that he might be picked off by a passing hawk or stray dog, and tried to encourage him to stay at home in safety, but the Rat roamed feckless and disconsolate, poking in the bottom of ditches with his silver topped walking stick, and shouting through the airbricks into the under-floor voids, his voice echoing and shrill.

‘Mouse? Mouse? Where are you Mouse?’

Then one night the Rat fell over something hard in the darkness near the meadow. Before he could pick himself up, a tiny wooden door set into the side of a hedgerow burst open and a fieldvole in striped pyjamas rushed out.

�

��Here, what d’you think you’re doing,’ shouted the fieldvole. The Rat felt his ankle, disconcerted to be addressed so rudely by a mere fieldvole. Fumbling in the dark he was surprised to find himself entangled in a length of chain which appeared to have been stretched over the normal path. The chain was painted black, with sharp ornamental spikes. His shin was bleeding.

‘You’re in my garden, Rat,’ said the fieldvole. The Rat looked around and yes, it was true, the fieldvole appeared to have made some attempt to organise the natural unruliness of the meadow by imposing a pattern of borders and cut grass here and there, arranged as if in a curious parody of human garden design.

‘What’s this fence?’ asked the Rat, throwing the chain links away contemptuously.

‘Its mine. The Cat said I could have this part of the garden, and I’ve taken it,’ said the fieldvole.

The Rat was even more taken aback.

‘Have this bit of the garden!’ he repeated. The entire concept was so alien as to appear barely comprehensible.

‘I’ve paid for it and it’s mine. Now, bugger off out of it.’

‘Paid for it,’ said the Rat, scratching his head, and overlooking the insulting tone the fieldvole had used. ‘What with?’

‘I’m not telling,’ said the fieldvole, mysteriously.

‘Rubbish,’ said the Rat, and crossly began to pull up the chain link fence, post by post, out of the ground.

‘I’m not having it,’ he said. The fieldvole looked on, rocking on his heels.

‘You’ll see,’ he said, knowingly, as if confident that the Rat would be swiftly and effectively punished.

The Cat observed the encounter from a partly shaded upstairs window, drinking from a whiskey tumbler he had found which had rolled under the bath. Soon everything would be different. Already in the dusk he could see several minute pinpricks of light flickering, small beacons of hope within a sea of darkness and animal squalor. These were the homes where he had support; the doors of burrows and shelters newly painted and barred against the night. There was beginning to be quite a different spirit in the garden, a more satisfying indifference to the things that went on … that were going on, nightly.

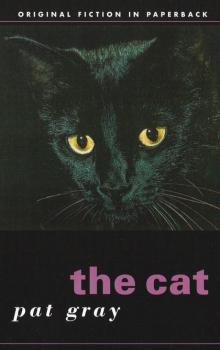

The Cat

The Cat